Detained Sudanese journalist on hunger strike

Journalist Ahmed Bishara El Dei, who was detained by Sudan’s National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) on July 16, has been on a hunger strike for five days, after his captors denied access to medication.

File photo

File photo

Journalist Ahmed Bishara El Dei, who was detained by Sudan’s National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) on July 16, has been on a hunger strike for five days, after his captors denied access to medication.

El Dei was detained for publishing a video condemning the bread crisis and the candidacy of Omar Al Bashir in the 2020 elections.

His brother Musab told Radio Dabanga that the security apparatus denied them delivering medicine to his brother Ahmed, who was suffering from gastric infection, explaining that his health condition is serious.

He held the security apparatus responsible for the life of his brother. He pointed out that his brother entered into a hunger strike five days ago in protest against the apparatus refusal to bring his medicine.

Press curbs

In June, journalists decried the draft Press and Publications Act which the Cabinet approved. It provides for the suspension of journalists from writing and the expansion of powers of the Press and Publications Council.

‘Red lines’

Earlier in August, newspapers and the head of the NISS agreed to form a committee to deliberate on the so-called red lines for Sudanese media. New confiscations of newspapers were temporarily suspended, while the work of the joint committee was pending. The security service did not say until when the temporary suspension is active.

In the preceding week the distribution of El Jareeda newspaper was purposely delayed by the NISS for six days in a row because of its critical content. It was the third time El Jareeda suffered from press curbs by the Sudanese security service in two weeks’ time: it blocked the newspaper from reaching the distribution outlets in Khartoum and the states.

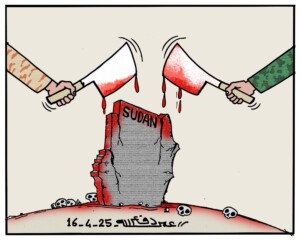

Media in Sudan are constantly subjected to attacks on press freedom. The country is ranked at the bottom of the World Press Freedom Index by the global monitoring organisation Reporters Without Borders (RSF).

and then

and then